Thousands of people are currently protesting in the high-altitude Ladakh region of India, braving sub-zero temperatures.

Last year, the government finally addressed their longstanding request for a region independent from Indian-administered Kashmir. However, starting from 2020, they have been regularly protesting on the streets, claiming that the government has failed to fulfill its promises and feeling betrayed. Srinagar-based freelance journalist Auqib Javeed provides an update on the recent developments.

Ladakh, located in the northern part of India, is a desert region with a population of around 300,000. The people living here belong to both the Muslim and Buddhist communities. In the Leh region, the majority of the population follows the Buddhist faith, while in the Kargil region, the community is predominantly Shia Muslims.

For years, the Buddhist community has been advocating for a distinct region for their people, while the residents of Kargil have expressed their desire to be part of the Muslim-majority region of India-administered Kashmir.

In 2019, the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi made the decision to revoke Article 370 of the constitution. This article had granted special status to the former state of Jammu and Kashmir, providing it with a considerable level of autonomy. The state was subsequently divided into two parts – Ladakh, and Jammu and Kashmir – and both are now federally administered territories.

After a year, Kargil and Leh districts came together to establish the Leh Apex Body (LAB) and Kargil Democratic Alliance (KDA), with the goal of addressing the concerns of the people. Civil society groups have organized large-scale protests against the federal government.

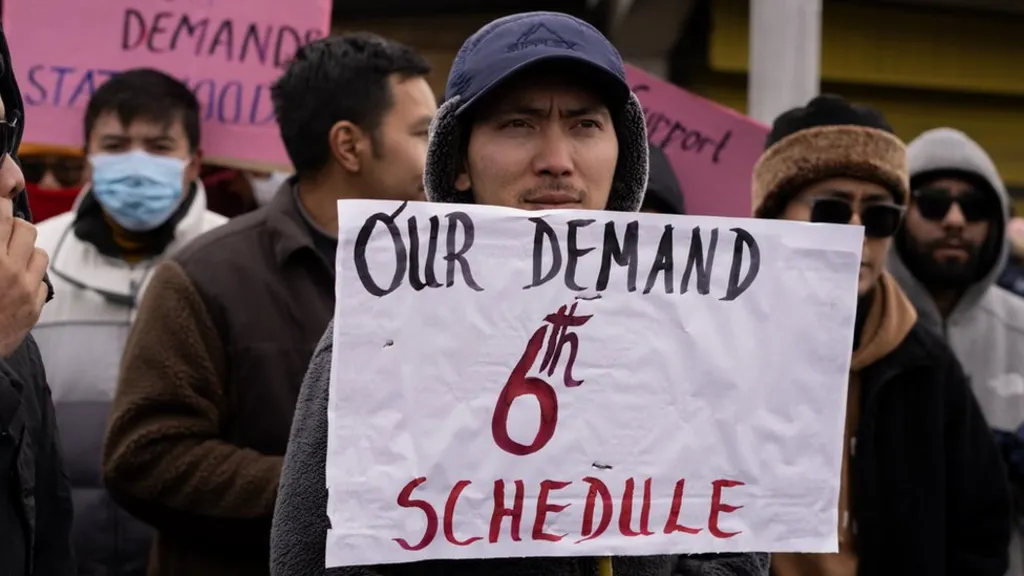

Earlier this week, there was a significant event in Kargil as shops closed and thousands of people took to the streets to voice their demands. Next week, a border march is being planned by protesters in Leh.

“We were advocating for the establishment of an independent region with its own governing body,” shares Chhering Dorjey Lakrook, a respected Buddhist figure from Leh. “However, we were only given a territory under federal governance.”

Concerns were raised among the residents of Ladakh, who rely heavily on agriculture, regarding the potential impact on the region’s culture and identity. The new policy raised fears that it would facilitate the purchase of land by outsiders.

As of 5 April 2023, the home ministry of India reported that there has been no investment from Indian companies in Ladakh over the past three years, and there have been no land purchases by external parties.

However, residents are still concerned about a potential increase in population, similar to what has been observed in Jammu and Kashmir. According to data, there have been 185 instances of outsiders purchasing land between 2020-22 in that region.

Their demands encompass various aspects such as statehood for Ladakh, employment opportunities, safeguarding their land and resources, and representation through a parliamentary seat for both Leh and Kargil districts.

In addition, they are advocating for the implementation of the Sixth Schedule, a constitutional provision aimed at safeguarding tribal populations and empowering them to establish autonomous organizations responsible for legislating on matters related to land, health, and agriculture. It’s worth noting that a significant majority of Ladakh’s population belongs to tribal communities.

“The Sixth Schedule was created with the intention of safeguarding the rights of indigenous and tribal groups,” states Chhering Dorjey Lakrook, the former president of the regional unit of India’s governing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) until 2020. According to him, this will protect them from being taken advantage of by business owners.

The federal home ministry established a committee to address these demands, however, locals express frustration over the lack of progress.

Young individuals in the area are also expressing their concerns regarding the lack of opportunities for employment in the public sector.

According to Padma Stanzin, the leader of Ladakh Students’ Environmental Action Forum (Leaf), there has been a noticeable absence of new senior government recruits since 2019. “We have concerns about the potential impact on our employment,” she adds.

Ladakh’s BJP MP Jamyang Tsering Namgyal did not provide a response when approached by BBC for comments.

Ladakh’s strategic location is of great importance to India, as it borders both China and Pakistan. These two nations strongly criticized India’s decision to revoke Article 370.

Although there was a prolonged armed uprising against Delhi’s rule in Indian-administered Kashmir in the late 1980s, Ladakh remained unaffected by the militancy.

During the 1999 Kargil war with Pakistan, the residents of Ladakh selflessly offered their support by providing food and other essential supplies to the Indian soldiers.

Residents are now questioning if their loyalty has come at a cost.

“The spirit of community involvement will be lost if the government disregards the people’s sentiments,” expresses Sonam Wangchuk, an engineer, innovator, and climate activist, who has dedicated years to addressing the needs of local communities.

Mr Wangchuk, who rose to prominence following the portrayal of a character inspired by him in the popular film Three Idiots, is currently undertaking a 21-day-long fast. His aim is to draw attention to the government’s commitments in protecting Ladakh’s environment and preserving its tribal indigenous culture.

The people of Ladakh have shown their support for Indian soldiers, including those from the plains who have faced challenges adjusting to high altitude. “Any disruption will affect this enthusiasm,” he adds.

China and Pakistan would closely monitor the situation in the region for any indications of vulnerability, according to experts.

“Unrest and discontent, particularly if it continues over time, is a potential area of interest for Beijing and Islamabad,” suggests Michael Kugelman, the director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Centre, a Washington-based think-tank.

Beijing did not acknowledge the establishment of Ladakh as a federally-governed territory in 2019. The region is located along a 3,440km (2,100 mile)-long de facto border in the Himalayas. This border, known as the Line of Actual Control or LAC, is poorly demarcated.

Since 2020, there has been a significant escalation of tensions between India and China. This was triggered by a clash between their forces in the Galwan river valley in Ladakh, resulting in the unfortunate loss of at least 20 Indian soldiers.

After the clashes, both Delhi and Beijing escalated troop movement and constructed extensive military infrastructure along the LAC. China has initiated incursions in Ladakh, asserting control over more than 1,000 sq km of territory that India claims as its own. India has consistently refuted China’s assertion.

The presence of Chinese soldiers in Ladakh and their interference with local residents’ herding activities have only fueled the existing grievances in the region.

In January, there was a confrontation between local herders and Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldiers when the herders were stopped from accessing their usual grazing lands near the LAC.

According to Mr Kugelman, India is facing the challenge of maintaining stability in Ladakh, but reversing the changes made in 2019 is not a viable option.

Delhi has consistently maintained that the repeal of Article 370 and the related actions would be conclusive, resolving any disputes and instability in the affected regions.

“Altering the status of Ladakh and granting it statehood could potentially undermine the current position and cast doubt on the decision made in 2019. This is not the impression that Delhi intends to convey,” he explains.

According to Praveen Donthi, a senior analyst for the International Crisis Group, a Delhi think-tank, India’s reluctance to grant more powers to the local government in Ladakh can be attributed to this reason.

“The LAC has become increasingly volatile following the Galwan clash, and it appears that the government is taking a cautious approach,” he remarks.

Ladakh residents are hopeful that their unity, demonstrated through joint action by the Muslim and Buddhist communities, will eventually lead the authorities to address their grievances.

“Our solidarity will ensure that the government listens to us and takes action on our requests,” states Jigmat Paljor, a student-activist in Leh. “It’s only a matter of time before they have to pay attention.”

More Stories

Trial for Rape and Human Trafficking will take Place in Romania for Andrew Tate and his Brother Tristan

A British individual tests the first Customised Melanoma Vaccination

Gaza Baby Delivered from Dead Mother’s Womb Perishes