During a rainy Tuesday afternoon, Yejin is preparing lunch for her friends at her flat, where she resides alone on the outskirts of Seoul, content with her single life.

While dining, one of them brings up a popular meme featuring a cartoon dinosaur on her phone. The dinosaur issues a warning to be cautious. “Avoid facing the same fate as us.”

The women burst into laughter.

“It’s amusing, yet sombre, as we are aware that we might be bringing about our own demise,” remarks Yejin, a 30-year-old television producer.

She and her friends have no plans to have children. They are members of an expanding group of women opting for a life without children.

South Korea’s birth rate is the lowest globally and keeps dropping, surpassing its own extremely low record annually.

Statistics published on Wednesday reveal a further 8% decrease in 2023, bringing it down to 0.72.

This indicates the average number of children a woman is projected to have during her lifetime. In order for a population to remain stable, the number should be 2.1.

If the current pattern persists, Korea’s population is projected to decrease by half by the year 2100.

A situation of ‘national emergency’

Internationally, developed nations are experiencing a decline in birth rates, with South Korea standing out as an extreme case.

The forecasts are quite bleak.

In 50 years, the working-age population is projected to decrease by half, the pool for mandatory military service will shrink by 58%, and almost half of the population will be over 65 years old.

This situation is extremely concerning for the country’s economy, pension pot, and security, leading politicians to label it as “a national emergency.”

For almost two decades, different administrations have allocated a significant amount of funds to address the issue – specifically 379.8 trillion KRW ($286bn; £226bn).

Families with children receive various financial benefits, including monthly allowances, discounted housing, and complimentary transportation services. Hospital bills and IVF treatments are included, but only for individuals who are married.

Financial incentives have proven ineffective, prompting politicians to consider alternative solutions such as hiring nannies from South East Asia at below minimum wage and exempting men from military service under certain conditions.

It’s no surprise that policymakers are facing criticism for not paying attention to the voices of young people, particularly women, regarding their needs. Throughout the past year, we have journeyed across the country, engaging with women to uncover the motivations behind their choice to not have children.

When Yejin chose to live independently in her mid-20s, she challenged societal expectations – in Korea, living alone is often seen as a temporary stage in life.

Five years ago, she made the decision to remain unmarried and childless.

She expresses difficulty in finding a suitable partner in Korea who is willing to equally share household responsibilities and childcare. Additionally, she notes that single mothers are often stigmatised.

In 2022, just 2% of births in South Korea took place without the parents being married.

‘A never-ending work cycle’

Yejin has decided to prioritise her television career, as she believes it doesn’t leave her with sufficient time to care for a child. Work hours in Korea are famously lengthy.

Yejin has a traditional 9-6 job (the Korean equivalent of a 9-5) but mentions that she typically stays in the office until 8pm with additional overtime. After returning home, she must choose between cleaning the house or exercising before going to bed.

“I adore my job, it brings me a great sense of fulfilment,” she expresses. “Working in Korea can be challenging as you find yourself in a constant cycle of work.”

Yejin mentions the pressure to study in her spare time to improve at her job. She explains that in Korean culture, there is a belief that continuous self-improvement is necessary to avoid falling behind and failing. This fear motivates us to put in double the effort.

“Sometimes on weekends, I go and get an IV drip, just to recharge before heading back to work on Monday,” she mentions nonchalantly, as if it were a typical weekend routine.

She also expresses a common concern among women I spoke with – the worry that if she were to take time off to have a child, she might struggle to re-enter the workforce.

“There is a subtle expectation from companies that once we become parents, we are expected to quit our jobs,” she explains. She has witnessed it occur to her sister and her two beloved news anchors.

‘I know too much’

A 28-year-old woman working in HR shared her experience of witnessing colleagues facing negative consequences such as job loss or missed promotions after taking maternity leave, leading her to decide against having children.

Both men and women can take a year off during the initial eight years of their child’s life. However, in 2022, just 7% of fathers took advantage of their leave, while 70% of mothers did.

South Korean women rank highest in education among OECD nations, despite facing the largest gender pay gap and higher female unemployment rates than men.

According to researchers, this demonstrates a trade-off between pursuing a career and starting a family. More and more individuals are opting for a profession.

I encountered Stella Shin at an afterschool club, where she instructs five-year-olds in English.

Take a look at the children. “Aren’t they adorable?” she gushed. However, at the age of 39, Stella does not have any children. She mentions that it was not a deliberate choice.

They have been married for six years, and both of them desired a child but were too occupied with work and having fun that time passed by. She has now come to terms with the fact that her lifestyle makes it “impossible”.

“Mothers should stay home to care for their child full time during the first two years, and this would greatly affect my mental health,” she expressed. “I enjoy my job and prioritising my well-being.”

During her free time, Stella participates in K-pop dance classes with a group of mature women.

It is common for women to be expected to take two to three years off work when they have a child. When I inquired about sharing parental leave with her husband, Stella dismissed me with a look.

“It’s as if every time I ask him to do the dishes, he manages to miss a spot. I just can’t depend on him,” she remarked.

She expressed her inability to quit her job or balance work and family due to the exorbitant housing expenses.

Over half of the population resides in or near the capital Seoul, where the majority of opportunities are concentrated, leading to significant strain on apartments and resources. Stella and her husband have found themselves moving away from the capital and into neighbouring provinces, struggling to purchase their own home.

Seoul’s birth rate has dropped to 0.55, the lowest in the country.

Next, we have to consider the expense of private schooling. While unaffordable housing is a widespread issue, Korea stands out for its unique approach.

Starting at the age of four, children attend a variety of costly extracurricular classes, including maths, English, music and Taekwondo.

It is so common that choosing not to participate is viewed as putting your child at a disadvantage, which is unthinkable in highly competitive Korea. This has made it the priciest country globally to bring up a child.

In a recent study conducted in 2022, it was revealed that just 2% of parents did not invest in private tuition, with a staggering 94% expressing that it posed a financial strain.

Being a teacher at one of these cram schools, Stella is familiar with the burden. She observes parents investing up to £700 ($890) per child monthly, even though many struggle to afford it.

“But in the absence of these classes, the children lag behind,” she remarked. Being around children makes me want to have one, but I feel too informed to make that decision.

Starting at the age of four, Korean children are enrolled in a wide variety of extracurricular activities

For some individuals, this system of costly private tutoring goes beyond financial implications.

“Minji” wished to share her experience, but preferred to keep it private. She is hesitant to share with her parents that she does not plan on having children. “They will be very surprised and let down,” she remarked, from the coastal city of Busan, where she resides with her husband.

Minji shared that her childhood and 20s were not happy.

“I’ve dedicated my entire life to studying,” she remarked, striving to secure a spot at a prestigious university, preparing for her civil servant exams, and eventually landing her first job at the age of 28.

She recalls her early years in school, staying up late studying maths, a subject she disliked and struggled with, as she dreamed of becoming an artist.

“I’ve had to compete endlessly, not to achieve my dreams, but just to live a mediocre life,” she expressed. “It’s been quite exhausting.”

It’s only at 32 that Minji finally feels liberated and can fully embrace her life. She enjoys exploring new places and is currently mastering the art of diving.

However, her primary concern is avoiding subjecting a child to the same intense competition she went through.

According to her, Korea is not a suitable place for children to live happily. Her husband has now come to accept her wishes regarding having a child, after they used to constantly argue about it. Every now and then, she feels uncertain, but she quickly recalls the reasons why it’s not possible.

An unfortunate social occurrence

In the city of Daejon, Jungyeon Chun describes her situation as a “single-parenting marriage”. After collecting her seven-year-old daughter and four-year-old son from school, she explores the nearby playgrounds, spending time until her husband comes back from work. It’s unusual for him to get home before bedtime.

“I didn’t realise the impact of having children on my career. I thought I could easily go back to work,” she expressed.

However, the social and financial pressures quickly became overwhelming, and she was taken aback to realise she was now parenting solo. Her spouse, a trade unionist, did not contribute to childcare or household chores.

“I was filled with rage,” she expressed. “I was well-educated and taught about gender equality, so I couldn’t tolerate this.”

This is the core issue.

For the last 50 years, Korea’s economy has rapidly advanced, leading to increased opportunities for women in education and employment, allowing them to pursue their ambitions. However, traditional roles of wife and mother have not progressed as quickly.

Feeling annoyed, Jungyeon started watching other mothers closely. “I thought, ‘Oh, my friend who’s raising a child is also feeling down, and my friend across the street is in the same boat’ and I realised, ‘This seems to be a social phenomenon’.”

She claims to be in a single-parent marriage, Jungyeon

She started sketching her experiences and sharing them on the internet. “The stories were flowing out of me,” she expressed. After gaining popularity, her webtoon resonated with women nationwide, leading Jungyeon to become the author of three published comic books.

She now claims to have moved beyond feelings of anger and regret. “I just wish I had more information about the reality of raising kids and the expectations placed on mothers,” she expressed. Women are choosing not to have children because they are bravely discussing the topic.

Jungyeon expresses sadness over women being deprived of the joy of motherhood due to the difficult circumstances they may face.

However, Minji expresses gratitude for having control over her own decisions. We have the privilege of being the initial group with the opportunity to make choices. Having children was once considered a necessity. Therefore, we opt not to because we are able to.

If I could, I would have 10 children.

After lunch at Yejin’s flat, her friends are playfully negotiating over her books and other belongings.

Feeling worn out from life in Korea, Yejin has made the decision to move to New Zealand. One morning, she had a sudden realisation that she was not obligated to stay in that place.

After conducting research on gender equality rankings, New Zealand stood out as the top performer. “It’s a place where men and women are paid equally,” she exclaims, “So I’m off.”

I inquire with Yejin and her friends about what might persuade them to reconsider their opinions.

I am taken aback by Minsung’s response. “I would be thrilled to have children.” I wish I could have 10 of them,” What’s preventing her, I wonder? The 27-year-old shares that she is attracted to both men and women and is in a relationship with someone of the same gender.

Although Minsung (on the right) is in a committed relationship with a partner of the same sex, she is unable to conceive through the usage of a sperm donor.

In South Korea, same-sex marriage is not recognised, and unmarried women are restricted from using sperm donors for conception.

“Hopefully one day this will change, and I’ll be able to marry and have children with the person I love,” she expresses.

The friends highlight the irony of some women in Korea who desire to be mothers but are unable to do so due to the country’s demographic challenges.

It seems that politicians are gradually acknowledging the seriousness and intricacy of the situation.

In a recent statement, President Yoon Suk Yeol of South Korea admitted that the efforts to address the issue through spending had not been successful, highlighting that South Korea’s competitiveness was excessive and unnecessary.

The government has acknowledged the low birth rate as a “structural problem,” but it remains to be seen how this will be addressed through policy.

Last month, I had a chat with Yejin, who had been residing in New Zealand for three months.

She was excited about her fresh start, new friends, and her position in the pub’s kitchen. She expressed that her work-life balance has improved significantly. She has the flexibility to schedule meetups with her friends throughout the week.

“I feel much more valued in the workplace, and others are less critical,” she remarked.

“It’s discouraging me from returning to my place.”

More Stories

Flash Floods on Bank Holidays Damage roads and Railroads

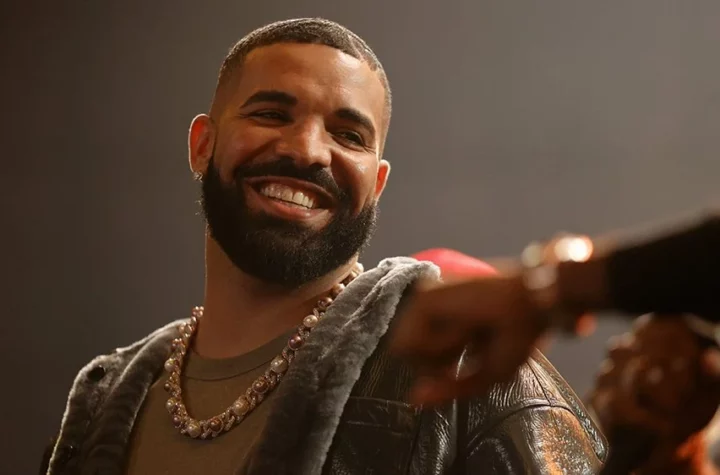

Drake Disputes Charges of Underage Relationships in Kendrick Lamar’s Song

A Presidential Poll in Chad is Expected to end Military rule